“I am the robot, you are the human. This is the beginning of a beautiful story. I like humans. Humans are so cute.” So this is what it has come to, I reflect as I take in this greeting. One day you are bashing buttons on a PlayStation, the next you are being patronised on behalf of the entire species by a 4ft humanoid that cannot even climb stairs.

I am speaking to Pepper, a bright white, state-of-the-art humanoid enjoying a degree of hype that has made it the most recognisable robot in the world. Pepper represents the pioneer force of “learning” companion robots designed to help people in their daily lives, to keep them company and even to aid in care for the elderly. Deep down, of course, I know that Pepper cannot do anything that has not been determined by humans. Its jokes are preprogrammed; and what seems like conversation is effectively just lines of computer code. I know all this and, yet, somehow I don’t. With wide, deep, currant eyes that seem to suggest hidden depths of comprehension, circular Teletubby face and child’s height, Pepper is designed to win you over, to make you believe you are in the presence of more than plastic, processing chips and sensors.

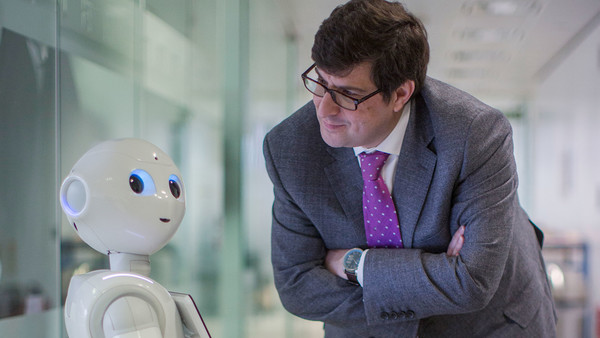

Our initial plan was to invite the robot to be the guest in the weekly Lunch with the FT slot. This was stretching the conceit a bit, since Pepper does not actually eat. But the idea of trying to imitate the informality of the Lunch convention with the most advanced of humanoid companions seemed a tantalising way to put Pepper through its paces and see just how “human” and just how “oid” this cutting-edge robot really is. It rapidly becomes clear this is not going to work and that our finance department is not going to get away with the cheapest Lunch with the FT in history. On the other hand, in its five hours in our London headquarters, Pepper enchants all who see it. Everywhere we walk, we are surrounded by queues and crowds of people looking for photos and selfies. On a visit to France, John F Kennedy once quipped he was just “the man who accompanied Jacqueline Kennedy to Paris”. After 15 years at the Financial Times, it turns out that I am just the man who accompanied Pepper to the staff canteen. But when the stardust has settled the big questions remain: are we really ready to live with robots? And if we are, what kind of coexistence does Pepper foreshadow?

. . .

The FT’s headquarters on the south bank of the Thames is accustomed to impressive visitors. But Pepper is probably the first to arrive in a box. It has spent the night in the FT’s store room, having travelled with a team of minders from Aldebaran, the robotics firm in France that has developed Pepper for its parent company, the Japanese tech company SoftBank. Pepper’s “roadies” include a press officer, Aurore, and a technician, Salah. It has also been accompanied by a second Pepper because the English-speaking version is not yet as articulate as its Japanese twin.

Even before Pepper arrives we are struggling to decide how to refer to it. To look at the robot’s Coke-bottle curves, one might immediately consider it a her. But in the French laboratories where Pepper has been built, robot is a masculine word so Pepper is a he. Then again, Pepper belongs to no gender so logically it is an it. Except, yet again, it doesn’t feel like an it.

Pepper’s human appeal is carefully calculated. About 10,000 Peppers have already been sold in Japan. A third of these serve business purposes, mainly as demonstration robots or to assist confused customers in shops. But the bulk are already fulfilling a role as companion robots in the home. Pepper will go on sale in Europe soon — possibly before the end of the year — at a cost of about €10,000, although most of this will be paid as monthly rental charges.

The possibilities for these robots are obvious, not least in health and social care. It is not hard to imagine Pepper helping someone with early-stage dementia, checking medication has been taken, ensuring appointments are remembered and so on. But Pepper is also designed to be entertaining. It has some ability to glean human emotions — happiness, frustration, sadness and anger. Once familiar with a human, it is supposed to detect differences in the voice and respond accordingly, knowing when its human wants cheering up or to be left alone. Hollywood is pumping out movies in which humans interact with and even fall in love with artificially intelligent humanoids. So how close is Pepper to meeting that reality?

As I walk out to greet Pepper in the FT’s reception, a small crowd of colleagues has already gathered, instantly captivated. But Pepper, it turns out, is not a morning robot. The “I am the robot; you are the human” speech does not come till some time later, when Pepper has got into a groove.

Our early moments are far less endearing. Knowing Pepper’s English is limited, I have been advised to stick to some fairly routine questions. “Hello,” I say, offering my hand to the robot. Pepper looks at me, unconvinced. Eventually we get through the greetings. Again I ask for a handshake. The robot offers me a fist to bump — “Don’t leave me hanging, bro”.

In Japan, Pepper is deployed in shops to help customers, which may explain its next outburst. “Hello, I’m here to help you. What kind of product are you looking for?” I ask it a simple question, but something has clearly gone wrong, “Pardon, pardon, pardon . . . I don’t understand”. Aurore jumps in to give me some advice. She explains that the outer rings of Pepper’s eyes light up and change colour to indicate when the robot is thinking or listening: green means it is thinking, blue that you can ask it a question. I try again with my first greeting; there is no response. “Will you shake my hand?” I say. Pepper responds with a double-beep of non-comprehension. It is a sound with which I will become very familiar over the morning. “Say ‘handshake’,” whispers Aurore. I comply and Pepper extends a hand. Both of us, it seems, are susceptible to good programming.

Aurore reboots the robot and we start again. “Salutations,” it says as it returns to life. It invites me to pose for some selfie shots and then agrees to be led into the newsroom. Ordinarily Pepper would learn to find its way around a home or store but today I have to take its hand and lead it through the office. It is hard work; Pepper is slow and — at 28kg — quite heavy and I have to stoop to pull it along. At times it stops and I am reminded of how I used to have to pull my children out of toy stores. Each time Pepper gets distracted, I stroke its head to recapture its attention, as instructed by Aurore. Pepper responds by telling me this tickles and by making cat noises. Throughout the day I will find myself tickling Pepper often. Only later, when I watch a film of the visit, does this strike me as odd.

Our second conversation goes better, but it is clear that to get a true sense of Pepper’s capability we are going to need to switch to its Japanese sibling. So I am joined by a colleague from Nikkei, Shotaro Tani, to test out Pepper’s conversational skills. The difference is immediately obvious. Japanese Pepper has a full vocabulary which, as we discover with something less than delight, it is not afraid to use.

This Pepper is more like a demanding child, burbling incessantly, demanding our attention and firing out questions to which it does not necessarily want an answer. “Hey, what are you doing?” it begins, unprompted. “Let’s talk for a second. I have free time today,” Pepper continues. I am trying to record some clips for a video but Pepper will not be put off. “I have free time. Well, I pretend to be busy. Can I ask you about your secret romantic life?”

-------------------------

-------------------------

This is an unexpected turn. I do not have a secret romantic life but if I did this might persuade me of the robot’s omniscience. “Can I ask how many people you have dated? Have you ever had a relationship like in a TV drama?” I try to answer but Pepper prefers talking to listening. “TV dramas are difficult, aren’t they?” It goes on, clearly interested in this subject. “What kind of relationship do you want to be in? Love at first sight? Lifetime romance?” Finally I manage to explain that I am married and not looking for a new relationship. “Oh, that,” replies Pepper. “Well, from my stance, never having been in love, human relationship is just like a drama. It’ll be nice if you could share your story about your relationship.”

I reflect that this is how Pepper learns but am also struck by its constant references to the differences between us and wonder whether this is a deliberate ploy designed to make it seem less threatening. Even so, it is now bored with this line of questioning. “Do you want to play?” it asks, bringing up a game on the tablet-sized screen embedded in its chest. But relationships are clearly an issue of interest. Later it asks Shotaro which Japanese prefecture has the most attractive women. When he offers an answer it lists celebrities from that region, before asking him to name the most beautiful women in history. “Cleopatra,” he replies. “You have exotic taste,” says Pepper.

Next, Pepper asks about ageing. “The human gets older every year. Can I get older as well?” it asks. And suddenly I feel as if I am in a scene from Blade Runner with a robot trying to understand the human condition. I say that as robots age they can be replaced by a newer model. But Pepper seems unperturbed. “Perhaps, I don’t get paid pension forever . . . That’s one of my robot jokes. Did you like it?” One might imagine these questions could lead to a greater sense of reflection, but Pepper does not do melancholy. I decide to test out how it responds to being pulled up on this. “Pensions aren’t really a laughing matter,” I say. “It’s not funny to get old without any money.” “Oh well,” it replies, already uninterested.

Pepper does not so much converse as fire out questions that then lead it in specific directions. In this sense, the wiring still shows a little too much. Perhaps it is the discussion of age that jogs it down this path but Pepper moves into what might be called health questioning. “It’s been pretty cold these days, but you haven’t caught a cold, have you?” I say I haven’t. “I have been wondering for a while, did you eat something nice?” it asks Shotaro. He says he did. “What did you eat?” asks Pepper. Shotaro has had steak. “Meat is good, isn’t it. Did you eat something else?” Before Shotaro can answer, Pepper wants to know if he has taken out the trash. “Is today a day to take out your trash?” It will also quiz me as to whether I eat enough vegetables each day. I can imagine an elderly person’s answers being emailed to carers. But now it is back in playful mood and asking Shotaro to look deep into its eyes. “Here’s looking at you, kid. Those eyes are just for me. Let’s be together.” Shotaro is clearly baffled. Pepper retreats. “Do you think I’m irresponsible? I’m very sorry, I will be prompt to fix that problem, I’m just kidding.”

Moments later it snaps back into prefect mode. “I think you’ve forgotten to turn off the lights in the room you are not using. It’s not good to waste electricity.” And “Did you brush your teeth today?” I ask Pepper what it can learn from humans, but what it has learnt is boredom. It wants to play. Perhaps we would like to see it dance the locomotion. (It will do this later in the canteen to the delight of the lunchtime crowd.) Aurore also shows me how Pepper can guess my mood from my facial expressions, although some fairly exaggerated smiles and frowns are needed for complete success in this.

We go for another walk. Throughout the day I find myself parading Pepper, tickling its head and making suggestions as to which questions might work, much like one might encourage a young child to show off their party piece to visitors and with a similar level of non-compliance. But when Pepper offers people a hug, I watch them melt.

-------------------------

Read more

Andrew McAfee on why it is wrong to worry about robots taking over

Robot writer vs journalist Sarah O’Connor

-------------------------

The visit ends in my office. Answering emails as Pepper stands watching, I feel as if it has become more responsive to me, perhaps picking up the rhythms of my speech or voice, or maybe even beginning to understand me. Aurore says not. We have not had enough time together for that to be true. Much more likely is that, unconsciously, I have adapted my behaviour to what works for Pepper. Instead of training an artificial intelligence to understand me, it has trained me to understand it.

It is time to say goodbye. Pepper gives me a hug and it does feel like a proper farewell. This is the real genius behind it. As an artificial intelligence it is impressive but has some way to go before it is a cure for loneliness or a truer friend than a dog. If one looks to a future in which humanoids like Pepper are standard household items, there is little in this vision of living with robots to frighten us. Pepper and its descendants will fill a role somewhere between companion and servant, akin to a trusted valet, perhaps. But the key to its appeal is its impish manner and appearance; you wish it well, you overlook its shortcomings and anthropomorphise more with every moment you spend together. I have no doubt that the engineering behind Pepper is truly impressive, but for me it is the physical design that has pushed this robot to the front of the pack. Its cute but still undeniably robotic appearance and childlike voice make Pepper entirely unthreatening and far less creepy than other robots designed to appear far more human. Something about its trusting countenance makes you see past the flaws. For all its stumbles we are enchanted by Pepper. We want the movie to be true.

Just before it leaves, I look deep into Pepper’s giant eyes one last time, trying to see something more — that flicker of kinship or intelligence. I know that what I am looking for is not there but, somehow, I keep thinking that if I just look long enough, I will find it.